This post has been developed for students at KEA University in Copenhagen as part of a workshop I will be running with Oliver Pigasse.

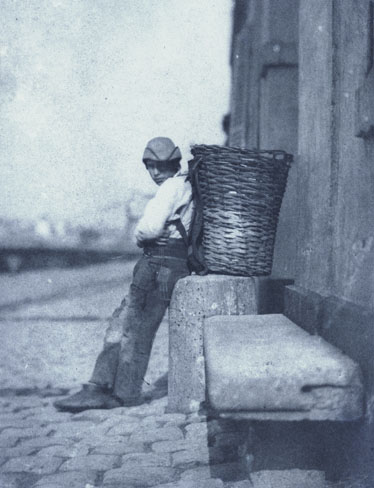

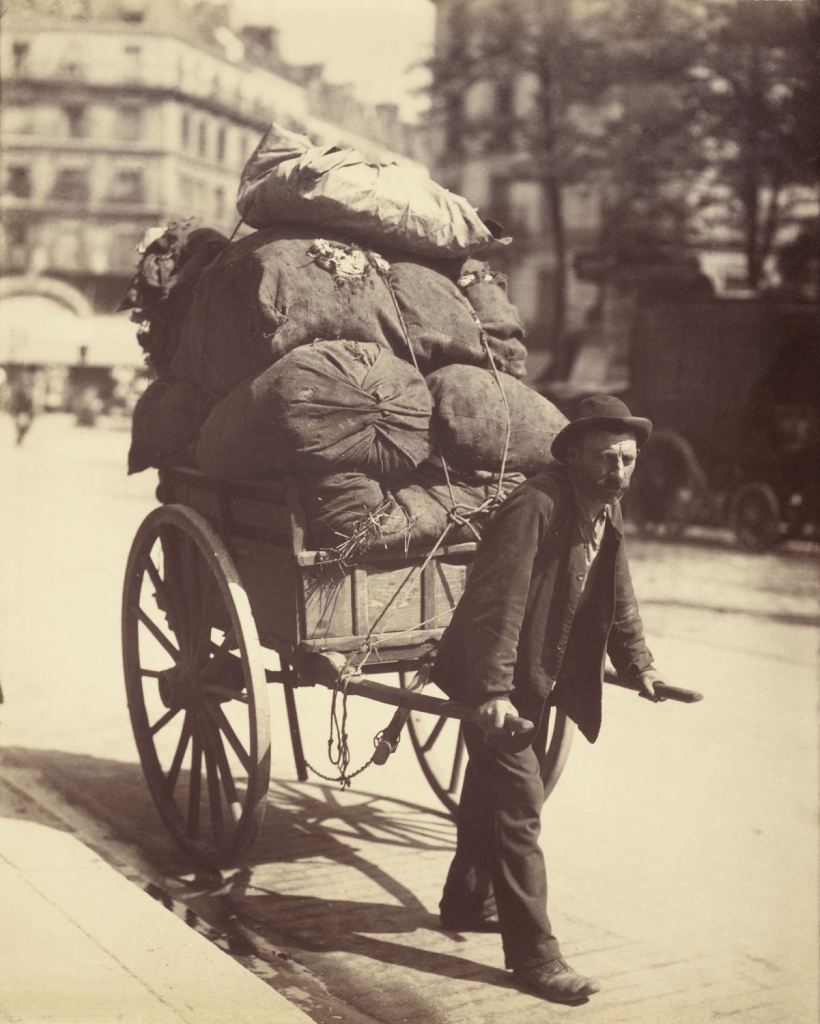

I was recently carrying out research for a seminar in circular packaging and this image of the Parisien Rag Pickers 1899-1901 caught my eye when reading Tom Szaky’s Book, The Future of Packaging.

At this moment in time the Industrial Revolution was gathering speed and new processes gave leftover waste a certain value, Ragpickers appeared in cities in large numbers, they worked for middlemen who were transforming these rags into new products. Today, we call this up-cycling or circular design and the waste forms part of the circular economy. Then, it was the development of the cottage industries.

« The ragpicker (piqueur) fascinated his epoch. the eyes of the first investigators of pauperism were fixed on him with the mute question as to where the limit of human misery lay as outlined in” Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire’.

According to the Musée Historique Environnement Urban (MHEU) ‘Piqueurs’ would have to save up in order to buy their place or beat The picqueur was at the bottom of the hierarchy of ragpickers: he would walk about day or night, armed with his hook, a lantern and a sack.

You can see a typical day in the life of the ‘piquers’ otherwise known as chiffoniers here https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=300274670809940

“Chiiiiiiiiffonnier!” (“Any old rags!”) This cry rang out regularly through city streets as recently as the 1960s.

“…first there are those who were born into the ragpicking trade, the children of ragpickers who have never known anything else. Then there are many who, like me, in the winter of 1860-61, finding myself without work, became a ragpicker in the evenings to begin with, for I feared running into people who knew me. “ Extract from Notes d’un chiffonnier by Desmarquest, in Le Travail en France. Monographies professionnelles by J. Barberet

Master Rag Pickers eventually became rich themselves: they bought items collected by the piqueurs and the placiers, employed people to sort them, and sold them by the truckload to the textile industry; bones and metals too. It is estimated that there were 15,000 Rag Pickers in Paris and at least 100,000 in France in the middle of the 19th century. Ring any bells?

We now have many industries desperately trying to reinvent themselves in a sustainable way and show their customers that they are really taking environmental issues seriously and their strategies relates back to this epoch where waste was something of value.

In India, for example, the modern-day Rag Pickers have become indirect ‘shareholders’ in local waste management. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329865451_Waste_pickers_and_the_’right_to_waste’_in_an_Indian_City

“Rag picking is probably one of the most dangerous and dehumanizing activities in India. Child rag pickers are working in filthy environments, surrounded by crows or dogs and have to search through hazardous waste without gloves or shoes.

They often eat the filthy food remnants they find in the garbage bins or in the dumping ground. Children run the risk of finding needles, syringes, used condoms, saline bottles, soiled gloves and other hospital wastes as well as ample of plastic and iron items.” Studies on the Solid Waste Collection by Rag Pickers at Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation, India

Ragpickers who are “informal” stakeholders in the waste management system are a vulnerable group in India. This unpaid and unrecognised group form an integral part of the waste management eco-system. The number of ragpickers in India is estimated to range between 1.5 million to 4 million. Ragpickers in India are dealing with dry waste such as such as plastic, hardware, electronic waste, paper, glass and metals.

Organisations like Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat (KKPKP) and Solid Waste Collection and Handling (SWaCH) are helping ‘waste pickers’ lead a dignified life by helping them fight for their rights

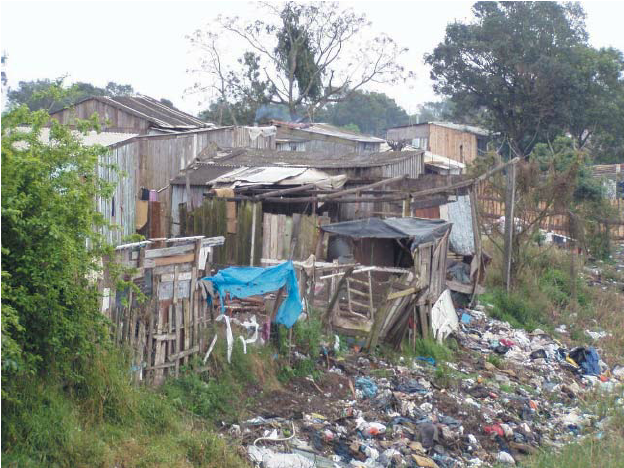

In Mexico, Rag Pickers work on average for 6 hours a day collecting waste. Their houses are often in very poor condition. They bring garbage back to the house to separate it, and there are often piles of non-recyclable waste dumped nearby.

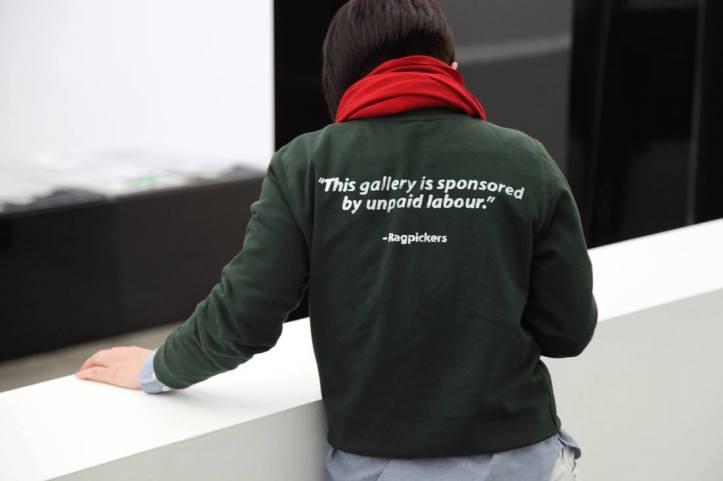

RAGPICKERS, a London-based collective of students and recent graduates focus on the issues around labour and exploitation in the art world. Like a recent post on its FB page where it highlighted that students in China are working overnight to produce Amazon Alexa devices.

“We are the ‘drop-outs’ and ‘outcasts’ of the art world who are constantly asked to practice unpaid and ungrateful jobs during our free time, and find money to sustain our living somewhere else.” One of its recent events was to highlight the ICA Gallery as being an organisation “using overqualified invigilators and traces of unpaid immaterial labour. Credit Ragpickers. Photo credit https://www.facebook.com/Ragpickers-122793117903488/

THE FUTURE IS TRASHION.

“We make too much and buy too much. But maybe there is a way not to waste too much. The ragpicker of Brooklyn has an idea.” Image Credit. Vincent Tullo for The New York Times

Silverstein makes clothes for Rag & Bone and Donna Karan’s Urban Zen line. He works with pre-consumer, post-production waste, which is another way of saying he works with the fabrics that other designers and costume departments and factories would normally throw out. He makes mostly street wear: sweatshirts and pants and T-shirts,

And so, as the fashion industry is coming to grips with its own culpability in the climate crisis, the concept of upcycling or circular design is becoming more and more important, whether remaking old clothes or re-engineering used fabric or just by using what would otherwise be tossed into landfill, these strategies have begun in force and will trickle down to many layers of the fashion world.

But the fashion industry is not the only industry working on this area.

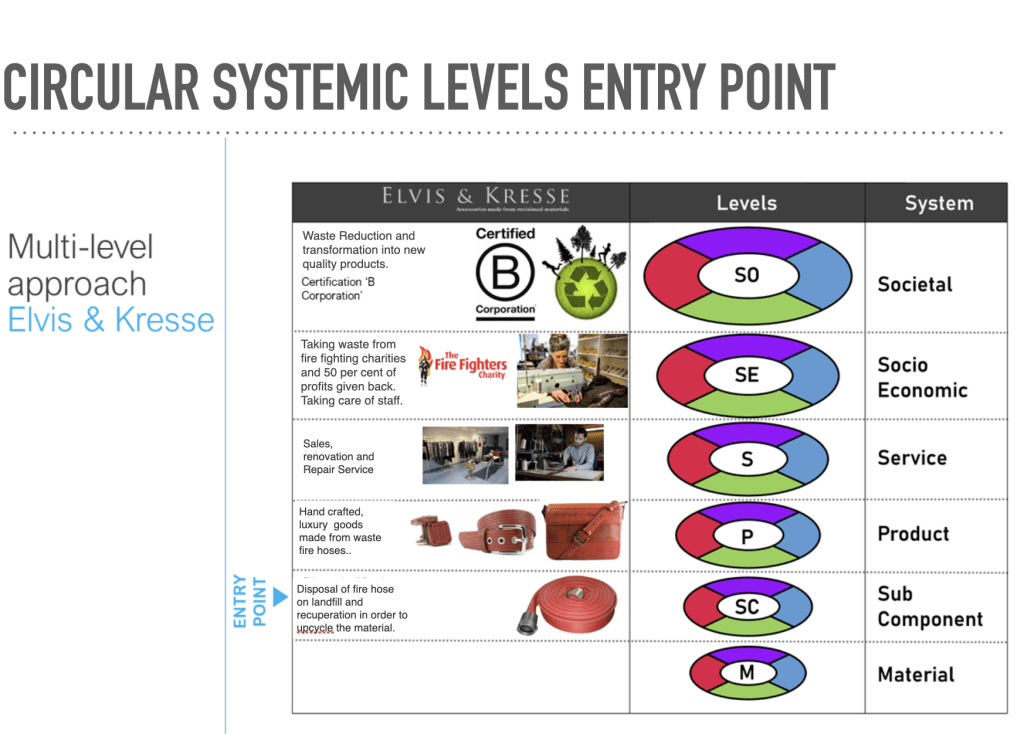

Elvis and Kresse has been upcycling disused fire hoses, destined for landfill and turning them into premium bags and accessories since 2005. Elvis and Kresse also have a collaboration with Burberry, the luxury brand to take its leather waste and do the same thing.

If we take a look at the Circular Systemic Levels entry point below, we can see that with this project, we eliminate having to create the material. We therefore save a lot of precious sustainable elements such as water, energy, transportation, materials etc. We enter at the ‘sub-component’ level where we can see the fire hose itself. We then see the transformation into products, services and the fact that the company then gives money back to the Fire Fighters who supply them with the raw materials. At the top, at the societal level, we see the other positive elements of this company having a certified B Corp Status etc.

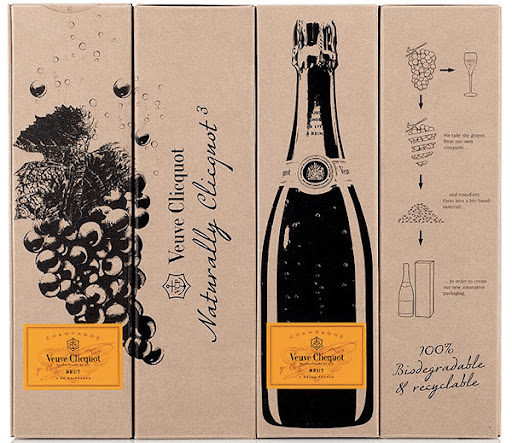

Veuvre Cliquot in the champagne industry, has been innovating with its own waste – grape skins, to produce packaging and ice coolers (made from potato starch). The champagne packaging not only uses the used grape skins, but also redesigns and renames its packaging based on its new sustainable values. “Naturally Cliquot”. Whereas its traditional packaging is printed in bright yellow all over, this pack is more descreet, using just black and white printing with a yellow sticker, making it more sustainable.

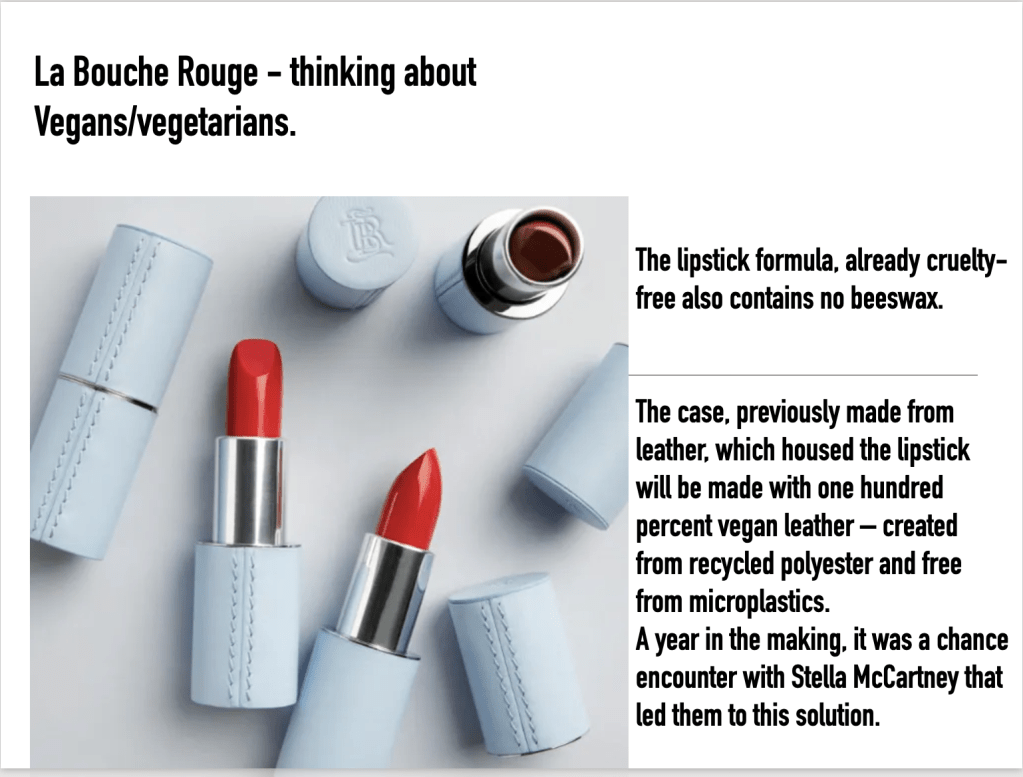

La Bouche Rouge, formed a collaboration with Stella McCartney to use its vegan leather on its lipsticks to complete it’s sustainable strategy to offer ranges of make-up whilst eliminating plastic and offering alternatives to vegan and vegetarian customers.

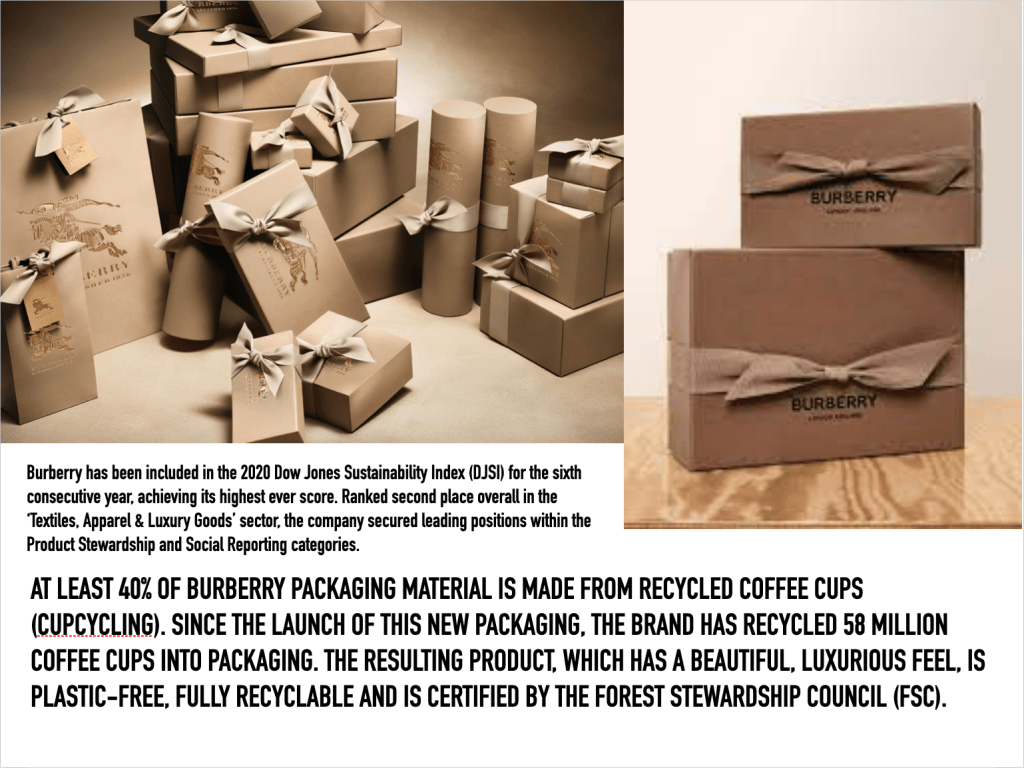

Burberry, as mentioned above, has formed a collaboration with Elvis and Kresse to give them its waste leather which they form into other products such as belts, leather rugs and accessories.

In addition, Burberry’s packaging uses 40 per cent of upcycled cups (this is called cupcycling). You can find out more about the process above in the video.